What Is a Conspiracy Theory?

Toward a definition

I did target a synagogue for a really good reason... Let’s be aware of the fact that the Jews promote the biggest hatred against Muslimeen even in the west. The Jews are in fact a very powerful group in the west which is why western countries today shill for them…

—Excerpt from the “manifesto” of thwarted New Jersey synagogue-attacker, Omar Alkattoul

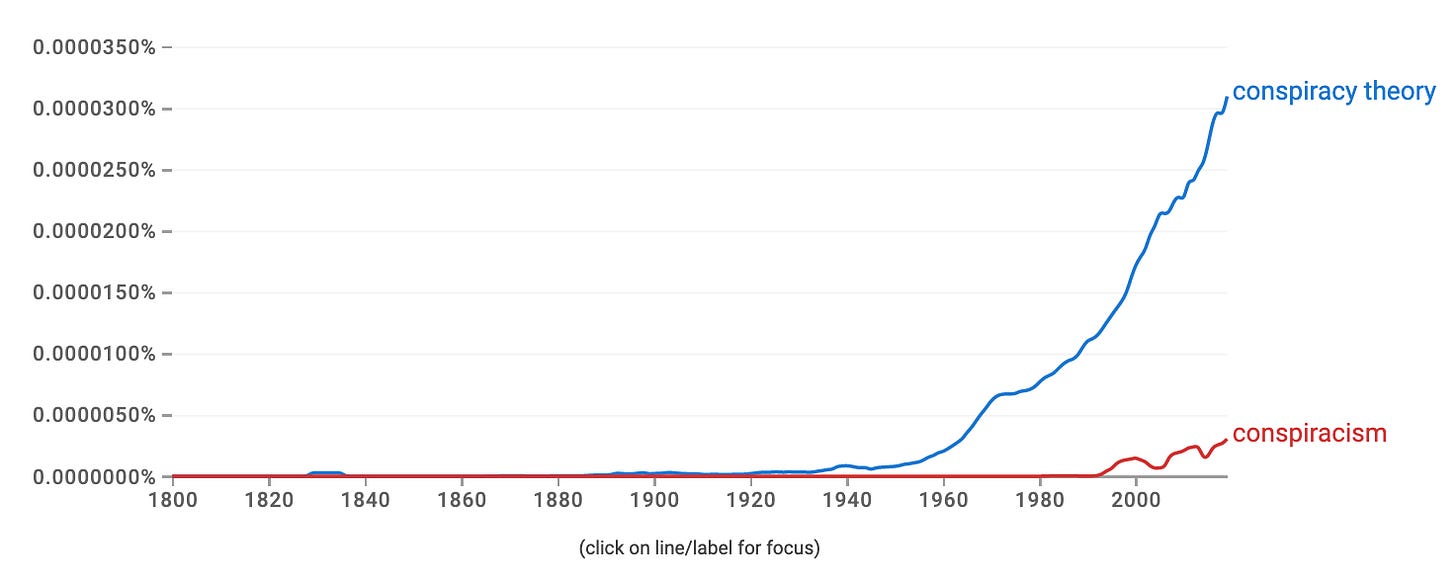

In seeking to define something, Aristotle urged us to identify its essence. Since the political rise of Donald Trump, there has been a great surge of interest in conspiracy theories, their various kinds, the people who believe in them, and—more recently, with incidents of mass murder, organized politics of menace, and the January 6th insurrection—their social and civic effects. There has also been much scrutiny, through lenses of psychology, sociology, and political science, of the nature of conspiracy theories and conspiracism—the underlying mindset that generates conspiracy theories as a framework for explaining the world.

This is an acute phase of a long-standing trend. Since the Holocaust—which was the apotheosis of conspiracism in history—scholarly and other, more serious literature on the topic has steadily grown.

But in all this time, we have no consensus on a definition that captures the essence of what is a conspiracy theory. Ultimately this is because the phenomenon is an example of what the Scottish philosopher W.B. Gallie described as an essentially contested concept. As with words like “justice,” “terrorism,” and “art,” we know it when we see it, but what we convey when we say “conspiracy theory” is abstract, complex, qualitative, and often laden with value judgment. These interpretive parameters frustrate agreement on the “proper general use of the term”.

When I began studying Antisemitism two decades ago, one of the first things that occurred to me was its essential nature as a conspiracy theory. While mundane anti-Jewish bigotry is always found, the form of Jew-hatred that is historically salient identifies “the Jews” as a preternaturally powerful, secretive, evil elite which enslaves and exploits humankind. Even a surface examination of conspiracy theories shows that while the identity of the elite changes, this narrative outline is common to all of them. Alternately—and with good reason we will explore later—Antisemitism is sometimes singled out as the ultimate conspiracy theory.

So we can better understand conspiracy theories if we widen our scope to include insights from the much larger literature on Antisemitism. The history of the “Longest Hatred” is an opportunity to examine more than a thousand years of the consistent social practice of a single conspiracy theory. In this vast and detailed record, we will detect patterns and peculiarities that expose the essence of the thing.

The definition I propose hence will leverage scholarship on conspiracy theories and conspiracism, but be situated in the living context of Antisemitism—the up-punching form of racism that is centrally rooted in the cultural heritage of the West and has done so much to shape its social and physical reality. This approach yields a dense definition, but one that is also—after some clarification of terms—comprehensive and empirically legible.

It is, as follows:

A conspiracy theory is a belief that a circumstance or event is a deliberate, connected, and occulted product of the timeless struggle between the forces of Good and Evil, attributable to the malign influence of a secret elite that supernaturally coordinates to enslave and exploit humankind, fabricates false consciousness to hide its activities, and indulges in pleasures and rites of extreme misanthropy.

In upcoming (though not necessarily contiguous) posts, I will clarify the terms I highlighted above and will also discuss three conceptual domains—Manichean, Epistemic, and Magical—in which many of the features and themes of conspiracy theories should be evaluated. I will explain and justify my definition over posts that I will specially mark for this purpose, so they become a series that readers can revisit and reference.

As a variety of racism, the historian Paul Johnson viewed Antisemitism as “so peculiar that it deserves to be placed in a quite different category.” Defining that peculiarity also helps to reveal what is a conspiracy theory—a mode of thought that is in some ways more corrosive than caste-based racism, but against which we’ve mustered no social movement to stigmatize and diminish it.